Oilfield decline rates matter.

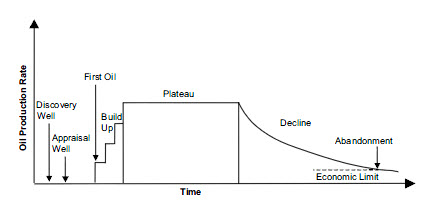

Every oilfield has a life cycle. An oilfield is born with its discovery, grows to adulthood through first oil & a ramp up to plateau production, before, in middle age, the rate at which it can produce oil begins to decline. Finally, in old age, the economic threshold is met, the pumps are shut down, the facilities removed, and the field dies.

Production from any oilfield begins to decline once it reaches middle age. Some fields decline faster than others – on average, small fields decline faster than large fields, offshore fields faster than onshore fields, and deep-water fields faster than shallow-water fields. Today, the world’s conventional oilfields that are beyond plateau production are declining at between 4.5% and 6.7% per year.

This matters, as before we can increase daily production to meet projected demand, we have to fill the gap left by declining production from today’s middle aged fields.

What’s the size of the decline production gap?

Assuming an average decline rate of 5% for conventional oilfields from this year (2013) means that in 5 years the industry will have to find ~18 million barrels of global daily production, just to fill the decline gap.

Can we do this? Well, probably… Let’s say the average new oilfield produces 25,000 barrels of oil per day (a pretty optimistic assumption*). That means that in a conventional decline rate world the industry will need to develop something like 720 oilfields over the next 5 years to fill the gap. Fields developed in this timeframe will stay on plateau for a few years after it. Assuming an average of 5 wells per field (1 discovery well and 4 producers/support wells) then we’re talking about drilling in the region of 3,500 wells. This ball-park figure is within the capacity of the modern oil industry. It’s pretty expensive though. At an average individual conventional well cost of $60 million dollars 5000 wells represents an investment of ~$220 billion dollars. That’s just drilling the wells, never mind the associated facilities & pipelines.

However, anyone who reads the papers will know that some of today’s replacement oil production comes from unconventional sources – primarily in the US in areas such as the Bakken, & Eagle Ford. This new production is revolutionising the American oil industry, and makes for a great media story. By 2015 the US may produce more oil than it has ever done before, exceeding US peak production of the 1970s. All because of unconventional oilfield technology.

In fact, Daniel Yergin, author of the excellent “The Prize” and the more recent “The Quest” suggests that most production will be from unconventional oilfields within 20 years, and the term will simply be forgotten. The unconventional will have become utterly conventional…

But one crucial difference will remain. Regardless of what you call them, unconventional oilfields decline more quickly than conventional fields. Not only that, but they do so almost immediately, with no plateau. In the absence of additional drilling, production from an unconventional oilfield can decline up to 40% every year.

So what would the challenge of filling the production decline gap in an unconventional world look like?

If all the world’s oil production was from unconventional oilfields, and oilfield decline was 40% per year, then over the next 5 years the industry would have to bring online something like 75 million barrels per day of new, additional production, just to meet today’s demand. That’s a huge production gap.

But it gets worse. Unconventional oil fields typically produce less per well than a conventional oilfield, and they don’t have a plateau production rate, but instead immediately decline.

If we assume an unconventional well produces ~100 barrels a day during the first 5 years of its life, as the mix of producing wells in the Bakken do today (mean peak initial production is ~400 barrels, but drops off rapidly), then replacing the 5 year unconventional decline rate would require ~750,000 wells. That’s lot of drilling!

In 2012 the white-hot US oil industry drilled just under 50,000 wells, using around 2000 rigs. If the world were to need 750,000 wells just to keep pace with current production then we’d need an unconventional industry 15 times the size of that in the US today, with perhaps 30,000 rigs constantly drilling & 26 million workers** just to keep up with 2012 production rates, let alone improving on them…

The unconventional oilfield revolution is an amazing story. However, it is not a panacea for all of our ills. The more we come to rely on unconventional oil production, the more we expose ourselves to a very rapid fall-off in future production. Today looks better at the expense of tomorrow. In an unconventional world we will need to keep running ever faster, drilling ever more wells, just to keep up with decline. And if we ever stop production will drop off a cliff almost without warning, preventing us from moving to any potential alternate energy solutions in a timely fashion.

Short-termism and unconventional euphoria could become a fatal danger if we lose sight of the implications.

It’s fine to celebrate unconventional technology in the short term. It is a great story, albeit with some real environmental issues that need to be managed responsibly. But we should not think that unconventional oilfield technology protects us from the future. Decline still matters. We’ve bought ourselves a bit of time today at the expense of warning time tomorrow.

* You could argue that it is just 1/10th of this rate. As there are around 40,000 oilfields in the world, and ~85 million barrels of oil per day production, the average production is 85 million/40,000, or about 2100 bpd. This represents some very old oilfields however, and is unlikely to apply to modern fields…

** As an aside, it’s interesting to look at the economic impact of unconventional oilfields, and their decline. Today the unconventional revolution in the US supports approximately 1.7 million jobs, rising to 3 million by 2020. It added around $62 billion to federal and state government revenues in 2012, which could rise to $113 billion by 2020. However, at 40% decline rates the unemployment & fiscal fallout would be rapid and chaotic if drilling was to stop, or even slow… Can anyone say Bodie, California?

Pingback: The Oil End Game? | The View from the Mountain