Just a few months ago, in October 2012, USA Today ran an article predicting that the US would overtake Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer in 2020. The article noted that during 2012 US production averaged 10.9 million barrels per day and that the Energy Department predicted an increase to 11.4 million barrels per day in 2013, just below Saudi Arabia’s output of 11.6 million barrels.

Instead, just a few months later, the US has already taken the #1 slot.

As the Carpe Diem blog has pointed out (hat-tip FT Alphaville), US total oil supply in January was greater than Saudi Arabia’s for the third month running. Today, the US is the world’s #1 producer, producing 11.56 million barrels a day vs. Saudi Arabia’s 10.85 million bpd.

US production growth has been faster than predicted, whilst Saudi Arabia is producing less, dropping by almost a million barrels per day.

This is a great technological success story, the result of the now famous fracking technology. That it happened in the United States is testament to the entrepreneurial spirit of the country (although the environmental issues are significant & will need to be managed).

For those who like to read the small print, note that the EIA’s “Total Supply” is defined as:

“production of crude oil (including lease condensate), natural gas plant liquids, and other liquids, along with refinery processing gains or losses.”

(this is important, as most of Saudi’s production is genuine crude, which is more useful and often more valuable…)

If you’d like to view the data with your own eyes and make your own comparisons, or download the digits for additional analysis, then take a look at the EIA website. It’s pretty confusing to navigate, but the data series can be found here. It will be updated monthly, so you can keep coming back for updates.

I noticed on the Carpe Diem blog some comments that disparaged the concept of Peak Oil because of this recent production. As impressive as the production turn-around is, I’d be a bit more cautious. The truth is, right now, we don’t really know.

A few other data-points stand out:

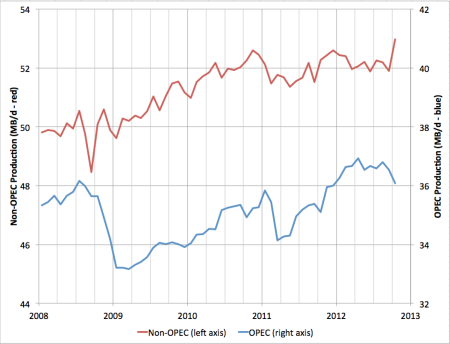

Non-OPEC production, of which the US is part, seems to have broadly flat-lined since mid-2010. Sure, it’s not a long time-series, but it seems that surging unconventional oil production from the US is simply offsetting production declines elsewhere.

Production decline in conventional Non-OPEC oilfields is illustrated by a graph of total oil production by the 5 oil majors (BP, Total, Chevron, Shell. & Exxon).

This appears to illustrate that production by the oil major’s peaked around 2004. The majors have been unable to offset this decline with “easy” conventional oil, and are less exposed to unconventional oil than the independents.

Easy, cheap, conventional oil production is perhaps peaking. Sure, unconventional oil production is increasing, but it is expensive and is failing, to date, to increase production on a global scale.

However, US production has not gone un-noticed. Saudi Arabia, historically the world’s number 1 producer, has been relegated to 2nd place, somewhere it hasn’t been since it shut-in production to support oil prices during a period of demand destruction subsequent to the dot-com bust at the turn of the century.

In contrast to Non-OPEC production (which generally keeps the pumps on full to make as much money as possible), OPEC chooses to shut in some capacity to support prices. OPEC spare capacity was running at just under 3 million barrels per day at the start of 2013. This is a marked increase vs. mid-2005, when spare capacity was less than 1 million barrel, but nowhere near the peak of over 6 million barrels in 2002 the last time Saudi Arabia produced less than the US.

Perhaps as a reaction to this, Saudi Arabia has just announced plans to increase their production capacity from 12.5 million barrels a day to 15 million barrels a day by 2020. The Saudi’s appear to value their position as swing producer and believe that a capacity increase is required to offset global decline and the threat of the US unconventional technology.

Will additional Saudi spare capacity simply offset oilfield decline elsewhere, or will it genuinely be additional, and perhaps be used as a weapon to undercut expensive US unconventionals? What will happen when unconventional technology spreads from the US? Can it really be replicated at scale elsewhere? How much can the US unconventional industry grow? What happens when it is a mature business? All these questions, and the future growth of global oil consumption, remain unclear.

And don’t forget that unconventional oilfields decline ten times faster than conventional oilfields. We may have kicked the can down the road, but Peak Oil hasn’t gone. We will need to move beyond oil at some point.

We still need an exit strategy.