Given the constant flow of news from Syria regarding the civil war, and today’s assertion that the regime has used chemical weapons, I thought that it might be a good moment to look at the Syrian oil industry, and its role in the conflict.

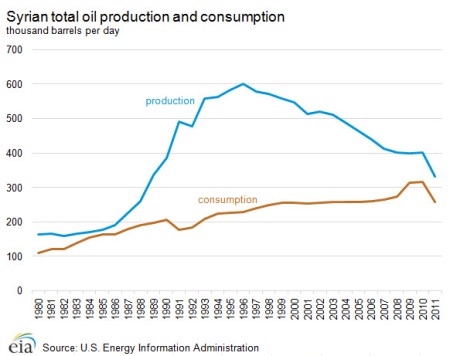

Oil has historically been an important source of revenue for the Syrian government, despite relatively low production. Oil production actually peaked at ~600,000 barrels per day in the mid-1990s, declining to ~400,000 bpd in the months before the conflict, but the $4 billion it brought in during 2010 still represented 35% of export revenues.

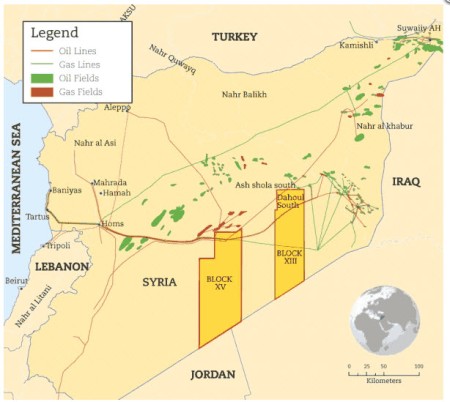

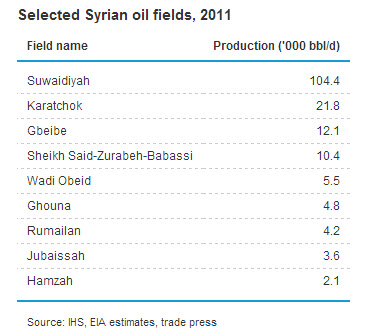

Syrian proved reserves were approximately ~2.5 billion barrels as at Jan 1st 2013. The bulk of Syria’s oil and gas fields run in a northeast – southwest band through the centre of the country, running from the city of Homs to the Hassake region in the very northeast corner of the country, bordered by Iraq and Turkey. Fifty percent of pre-war production was from this northeastern region, with the largest producing field in the country, Suwaidiyah, producing just over 100,000 bpd. The oil was transported along a major pipeline running to Homs and then on to the Mediterranean coast and eventual export.

There is a suite of smaller fields in the east of the country, trending northwest – southeast just north of the Euphrates river near the Iraqi border, in the Deir al-Zor region.

Syria’s oil is typically heavy and sour, making refining difficult and expensive. The smaller oilfields in the Deir al-Zor region are of a more refinable light crude. Syria has only two refineries, one in Homs and one on the Mediterranean coast at Banias. Most Syrian oil was exported to the European Union for refining, with Syria re-importing refined products such as diesel or petroleum for local use. Consumption has risen steadily since the 1980s, getting to within 80,000bpd of production in early 2011, thus restricting and complicating the country’s finances.

Since March 2011, Syrian oil production is down 50%, to an estimated 153,000 bpd. Oilfields were reportedly recognised by all sides early in the conflict as key to the country’s post-war wealth. Many fields were shut-in and remained broadly undamaged. However, in the first few months of 2013 violence related to oil infrastructure increased, with rebels securing oil installations and pumping stations amid fierce battles. Pipelines have also been damaged, particularly near Homs. Two international pipelines connect with Iraq, but only one remains in operation, the Ain Zaleh – Suwaidiyah pipeline, connecting Iraq with northeast Syria.

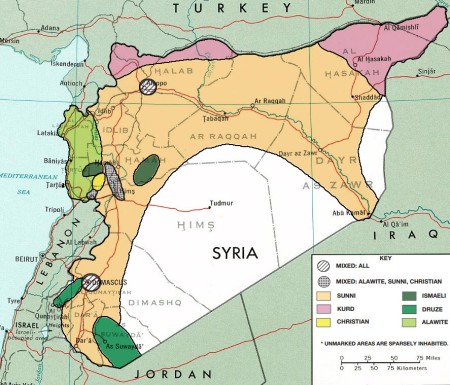

A map of ethnicity provides some interesting context. The government is dominantly from the Shi’ite Alawite sect, which is strongly concentrated along the coastal region of the country, away from sources of oil. East of the city of Homs the country is dominantly Sunni, until you reach the far northeast of the country, around the Suwaidiyah oilfield, which is dominantly Kurdish (most Kurds are also Sunni, but of different ethnicity).

Oil remains critical to the conflict as the government’s military fleet largely runs on diesel or gas oil. Subsequent to imposition of sanctions in 2011, when the EU ceased to purchase exported crude, the Assad regime resorted to bartering what crude production they could still access with countries like Russia, Iran, & Venezuela, swapping the oil for refined diesel.

In March, Syrian Sunni rebels surrounded the city of Deir al-Zor. The fighters responsible for the siege include fighters from Jabhat al-Nusra, some of the war’s most battle hardened and effective soldiers. The 10,000 strong faction is led by leaders of al-Qaeda in Iraq & publicly declared support for al-Qaeda earlier this month. The ranks include jihadist fighters from across the Islamic world and their stated aim is an Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Whilst the relationship between jihadists and local Sunnis is often wary, al-Nusra is winning hearts and minds by production and distribution of bread and oil across the region. The group is already in control the Deir al-Zor oilfields.

In the northeast of the country government forces withdrew from the oil town of Rumeilan between October 2012 and January 2013. Today, Kurdish fighters known as the Popular Protection Units (YPG) or the Democratic Union Party (PYD) control the region, fighting government forces and, on occasion, other Syrian rebels. Many locals claim that they want to secure a broadened autonomy for the region, which they call Western Kurdistan.

On the 22nd April 2013 the European Union lifted its oil embargo, aiming to provide support to forces fighting Assad’s government. But how can the oil get to market?

The existing Syrian pipelines pass through government territory on their way to the Mediterranean coast. There is a refinery at Homs that could perhaps provide some local products, but it remains in a disputed area with no clear control.

Turkey is directly opposed to Kurdish separatism and is unlikely to allow transport of oil into Turkey from Kurdish controlled Syria. Although it should be noted that, in a moment of realpolitik, Turkey has allowed oil shipments from Iraqi Kurdistan to pass through the country and talks continue between Kurds and Turks.

The Ain Zaleh – Suwaidiyah international pipeline does exist, but is designed for flow from Iraq to Syria, not the other way around. Crude could perhaps be trucked to Kurdistan, but would be vulnerable to government and (possibly) Turkish sponsored sunni groups.

Sweeter crude from the Deir al-Zor region could be trucked to Iraq and sold, directly supporting Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State of Iraq & the Levant.

Syria remains an extremely complicated situation. To summarise:

The heartland of Assad’s (Shi’ite) Alawite regime is along the Mediterranean coast, away from the oil reserves. Assad’s regime is starving of oil and diesel, relying on barter with Russia, Venezuela, & Iran and dwindling access to crude oil to fuel their military.

The oil regions themselves are split between Sunni and Kurdish control

The northeastern oil reserves are within an ethnic Kurdish area, with many locals supporting the idea of Western Kurdistan. The Kurdish regime in northern Iraq is supporting the Kurds in northeast Syria, and presumably the Turkish Kurdish groups are doing the same thing. However, whilst Turkey supports the Sunni Syrian rebels in general, it opposes Kurdish independence. Clashes in the Kurdish town of Ras al-Ain between Kurdish fighters and Sunnis are a sign of direct Turkish involvement in the area, according to Hamid Hajji Darwish, a leader of the Kurdish National Council.

The remainder of the oil discoveries are in Sunni areas, with the sweeter crude (and some gas) controlled by jihadist fighters loyal to al-Qaeda in their fight for an Islamic state across Iraq and the Levant. Some parts of Iraq may well support the Sunni groups.

Lebanon, bordering Syria to the southwest, is already split along sectarian Sunni and Shi’ite lines, and is likely supporting both sides in the civil war. It is at constant threat of being dragged into a more regional war.

Iran is a Shi’ite supporter of the Assad regime and a controller of Hezbollah in Lebanon and beyond, and of course it is playing its own regional game.

Sitting at the bottom of the map is Israel, paying close attention, and worried about Syrian supply of chemical weapons to Iran-controlled Hezbollah as the regime starves of fuel and foresees its own demise. Israel has already attacked a convoy in southern Syria for just that.

Simple, eh?

Keep your eye on the oilfields. If the rebels, Sunni or Kurd, can access & export crude, and thus gain cash, fuel, and additional armaments, then the balance of the war could shift significantly.

(p.s. just after I published this I saw that Syria is quite upset at the lifting of the oil embargo).

_______________________________________________________________

Postscript:

What caused the war? Why now?

You may have already read my post on oil, base rates, food, and the Arab Spring. The idea applies to Syria too.

It is interesting to note that during the early months of the Arab Spring Syria was considered a dormant, silent state, safe from revolution.

Then, by March 2011 the first demonstrations started. Why?

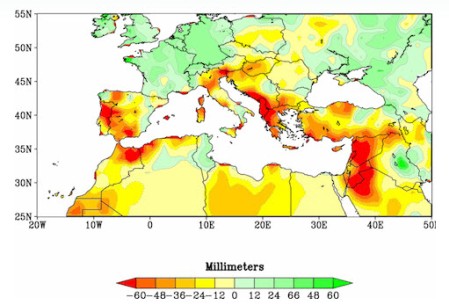

For much of 2006-2011 the Syrian region had experienced significant drought, heightening through 2011. Nearly 75% of agricultural land suffered crop failure. Herders in the Kurdish northeastern region lost 85% of their livestock, affecting 1.3 million people. Farms were failing, and people were suffering. In 2010 the New York Times ran an article describing the “fertile fields as turning barren”. Two to three million people were pushed into extreme poverty. Syria, the origin of wheat and barley, was forced to import grain, paying international spot prices.

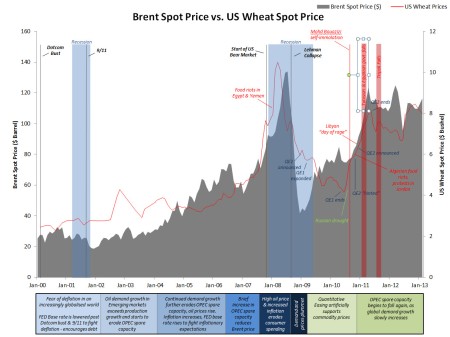

Then, between 2010 and 2011 the price of wheat doubled. US wheat prices reached almost $8 a bushel in March 2011, the month that protests erupted in Deraa, one of the poorest towns in southern Syria, and the subject of significant inward migration from the failing agricultural regions. When you’re poor and the price of food doubles, what do you do? What have you got to lose?

Interestingly, a NOAA study in the Journal of Climate links the prolonged drought to climate change, although mismanagement of water resources and the building of damns across the Euphrates are also clearly issues.

To throw a question out there, is the war in Syria the result of external pressures? The population has been subjugated and under emergency law for over 40 years. Why now?

Did two key events interact?

Did Western debt and the collapse of the financial industry (the result of soaring oil prices and possibly the first peak oil recession), lead to quantitative easing & the flowing of cheap money into commodities, and thus cause increased wheat prices?

And did the Syrian drought (possibly caused by global warming), lead to devastation of agricultural crops, mass internal migration, poverty, and the creation of a surge of agricultural Sunni’s into Alawite coastal towns, exacerbating disaffection within Syrian cities?

Did these two trends cause a civil war? Does this really boil down to our inability to produce sufficient oil in the mid 2000s and our continued production of CO2 to date?

Is this, in short, a taste of the future?